- Enjoying the Etymology of Whales

Masao Uchibayashi

Chairman / Takeda Science Foundation - Stranded whales in the culture and economy of medieval and early modern Europe

Klaus Barthelmess

Whaling historian and collector / Whaling museum consultant - Whaling in Korea and issues after the moratorium

Chang-Myeng Byen

Chairman / Korea Re-whaling Promotion Forum - Homage to Late Mr. Akiyama and Expectation for Prof. Koizumi

Yoshito Umezaki

Fisheries Journalist / Secretary of the Group to Preserve / Whale Diet Culture

ISANA Jul. 2003 No.27

index

ISANA Jul. 2003 No.27

Enjoying the Etymology of Whales

Chairman

Takeda Science Foundation

Gelatin, known as an edible substance, has been made from skin, bones and sinews of cattle, pigs and sperm whales. Lately, use of cattle products has been refrained in the wake of the mad cow disease. Further, using whales as main sources has become difficult because of the limited supply of whale products due to the international dispute of whaling in recent years. This represents one stage in which the world undergoes a drastic change.

The origin of the English word whale is found in the fact that the whale had been called *hwala- or *hwalis in the Germanic protolanguage, from which English had been derived. The fact that the Germanic race had a word denoting the whale is indicative of the position in which they were in the environment to encounter with whales in ancient times. The original inhabitation area of the Germanic people ranged from what are now northern Germany to Eastern Europe. Where had been their meeting point with whales? Or it might have been a vague name to call any large animals living in the sea.

Because the protolanguage of whales was *hwala-, or *hwalis (the h at the head of the word was silent frictional sound [k]), hwal came into existence in the Old English (1150 or before) and turned into whale in the Middle English (1150-1500). There had also been a word whall in the 14th and 15th centuries, which susbsequently went out of use.

From the same protolanguage hwal and walfisc (fisc means fish) were evolved in the Old Highland German (750-1050), which nowadays has become Walfisch in German.

The word baleine in French did not originate from the Germanic line. Almost all the European languages spoken today have evolved from the Indo-European protolanguage (born before 3000-2000 B.C.), which also includes Sanskrit in India. The Germanic protolanguage had been one of this Indo-European group.

In face of this changing situation, the anti-whaling bloc is criticizing Japan for buying the votes of developing countries in exchange for its Official Development Aid (ODA). But Japan is now extending ODA to more than 150 countries, among them being anti-whaling countries, such as India, Brazil, Mexico and Kenya. The reason for the increase in the number of supporting countries for the cause of Japan is that Japan's position based on scientific evidence has been accepted internationally.

(Note) The protolanguage is an assumed form of word type, and it has been a widely accepted practice to add the mark * at the head of the word to distinguish it from verifiable languages. The term "Indo-European" is abbreviated to IE hereinafter.From *bhel-, and *bhel- (meaning shining and white) of the IE protolanguage developed phalaina in Greek, and blaena, or blena in Latin. This was probably because people in olden times were amazed at the shining figure of a giant whale emerged on the surface of the sea in full sun light. This might have been the whale in the Mediterranean. The French word baleine comes from Latin.

Greek and Latin have another name for whales. *Qet- (meaning hole in the ground for dwelling, living space or living room) in the IE protolanguage was adopted, after some mutations in the meaning, as ketos in Greek, which became a general term indicating a giant animal in the sea, and later was specified as a whale. From this evolved the Latin word cetus. Cetus is used for various types of large marine mammals such as fur seals and dolphins, of course, including whales, even to this day. The family name for taxonomy of whales is Cetacea, and an alcoholic substance taken from whale wax is called cetyl alcohol.

Sperm whales which provided gelatin is called, in the botanical term, to be the order of Physeter catodon Linn. The genus name Physeter was taken from *phu- (meaning to blow and enlarge or blown and enlarged) in the IE protolanguage, and through *phu-s and *phy-s, was turned into physa (meaning bubble, water bubble, air bubble, or bellows) or physa (to blow or blow to enlarge) in Greek. From this word-stem "phys-" came phystr. This word denotes the sound generated at the time of blowing of steam from the whale's blow-hole (i.e. onomatopaeia such as pyu or fyu). Later it became the name for the blow-hole, and Linnaeus adopted it as the name of the genus. The sight of whale blowing steam so dramatically should have been very impressive. In modern Greek, phystr means a tube or wind instrument.

The origin of the name catodon, the species name of a sperm whale, is also interesting. This word is divided into cato- and odon. Kata and kat in Greek mean downward and the prefix kat- (cato- in Latin) also means downward. It is derived from IE protolanguage's *kmta (beside, along, or downward). Odon means a tooth in Greek, which is dens or dentis in Latin. Sperm whales (toothed whales) have corn-shaped teeth only in their lower jaw, and do not have whalebone or baleen in the upper jaw like baleen whales. Hence, the Latin word catodon means teeth only in lower part, which is a combination of kato and -odon. The word odon (tooth) comes from *ed (to eat) in the IE protolanguage and became odn in Greek through variations of *edont-, and *dont (teeth), and dens or dentis in Latin. In English, the medical science dealing with teeth is called odontology or dentistry, and tooth doctor is a dentist.

Physeter catodon Linn is called a sperm whale in English. In point of fact, this is an abbreviation of spermaceti whale. Spermaceti means whale wax. Ceti is a genitive case of aforementioned cetus and was combined with sperma (meaning sperm) to produce sperma-ceti (sperm of whale). It was later contracted as spermaceti. This naming is based on the belief that the white-colored solid wax or white wax taken from a sperm whale was solidified sperm of the whale. Sperm (sperma) has its origin in *sper- (to scatter, or sow seeds) in the IE protolanguage and became speir, speirein in Greek having the same meaning, and was turned into the Latin word sperma, becoming the English term sperm.

Now, we turn our eyes to the etymology of the Japanese name for whale. Makko kujira (sperm whale) was named so because the color of its body is like the brownish color of incense powder (makko). Makko is odorous powder made from agalloch and sandalwood, etc. and is used as incense at the Buddhist altar. Nowadays, it is made from the fine powder of leaves and skin of shikimi, Japanese anise-tree. In Japanese, there is a popular expression smell makko when you enter a Buddhist temple.

Let's look at the origin of the word kujira (whale). According to the Grand Japanese Dictionary published by in 1979 Shogakukan, the following explanations are given.

- (1) It comes for Kushishira (large animal). Ku is an old Korean term meaning big, and shishi (beast) and ra is a postfix.

- (2) Kuroshira (black and white). Its skin is black but it is white inside.

- (3) Kushira (queer),

- (4) Kojiru (to give much trouble) because it does not become calm easily after being caught

- (5) Kujira (to pick) because it hits the boat when emerging

- (6) Hakuhiro (one-hundred fathoms or a very wide span)

- (7) Kuchibiro (wide mouth) because of its large mouth.

The term kujira appears phonetically in Kojiki (712), Japan's oldest extant chronicle, recording events from the mythical age of the gods up to the time of Empress Suiko. It was also called kuji or okuchira.

We know the title of this publication ISANA. In olden times, whale was called isa. Iki-fdoki, the topographical description of the Iki region in 713, says: "People in this province call whales isa."

Further, in olden times fishes were called na as seen in old Japanese literature such as Nihon Shoki (720), the oldest official history of Japan covering events from the mythical age of the gods up to the reign of the empress Jito, and Man'yoshu (around 770), the earliest extant collection of Japanese poetry. Therefore, isana is the combination of isa and na, namely a whale.

As etymology of isana, the Shogakukan's Grand Japanese Dictionary enumerates: (1) isana (brave fish), (2) isona (whales near the beaches), (3) i is a prefix and sana comes from sosona (meaning a diving fish), (4) isana (a fish of 50 shaku long), (5) isana (unknown fish), i.e. fish inhabiting in the immeasurable depth in the ocean, (6) i is a prefix and sanatori comes from sunadori (meaning fishing).

From olden times, the term isana-tori (whalers) was used as a set epithet for the words related to the sea, beach and open ocean. We can find such expressions, as examples, in old Japanese literature such as aforementioned Nihon Shoki and Man'yoshu.

Finally, the Chinese ideograph for whale is pronounced [gyou] in Wuo sound, [kei] in Han sound, and [gei] customarily. Dividing the ideograph of whale into two parts vertically, the right half means big and strong while the left half meaning fish, so the combination of the two halves denotes a big and strong fish. That is a whale.

Stranded whales in the culture and economy of medieval and early modern Europe

Whaling historian and collector

Whaling museum consultant

The Japanese word "isana" is a perfect rendition of what we now call the psychological archtype of the "Great Fish", which in all maritime cultures is represented by the whale - analogous with the "Great Bird" or the "Great Land Animal", which in other societies may be represented by the eagle, condor, elephant, buffalo, bear, tiger, etc. Throughout history, all these animals have not only been the object of spiritual veneration, but also of material exploitation. Whenever such a Great animal by chance became available, the awe it inspired did not prevent humans from scavenging its big body for useful materials. Whereas the consumed protein resources from a stranded whale did not leave traces in history, both the material and the spiritual culture it inspired, have.

The earliest example of European poetry about a stranded whale is an Anglo-Saxon inscription on a whale bone casket of about 700 AD. The material is properly identified in Northumbrian runes: HRONSBAN, whale bone, and then follows the story of the beached whale and its plight. With some effort, experts of Anglo-Saxon culture have been able to discern an intricate system of runic magic in the inscriptions on this whale one casket. The explicit identification of the material strongly suggests, that magic properties were also attributed to whale bone. The high craftsmanship and the presumed magic aspects of material and inscription make it likely that the casket may have served as a container for precious gifts dealt out by a laird or warlord to his vassals in ceremonies intended to shape strong bonds of allegiance, something of utmost importance in early Germanic societies (for more detail see www.frankscasket.de).

Many sources testify to the economic importance of stranded whales to medieval maritime societies in Europe. Most are legal texts protecting the claims of feudal landowners to whales beached on their shores (as to wrecked ships). A Norman ruler of Sicily, Robert Guiscard (1015-1082) participated in the killing of a stranded whale and had the carcass distributed according to old Norse legal custom. Some 13th- and 14th-century sources from Britain give evidence that baleen was in demand for military (composite crossbows, armour plating, tournament swords, perhaps helmet plumes) and fashion purposes (garment stiffenings), but most of the supply was probably covered by imports from the organized inshore fishery for right whales carried out in the Bay of Biscay

In his huge manuscipt about animals of ca. 1260 AD, Albert the Great provides for the earliest reference to a series of sperm whale strandings in the North Sea - where this species only occurrs erratically - in the 1250s. Promoted to the art of literature the greasy topic is again by medieval poet Jan van Heelu. In his rhymed chronicle of ca. 1290 he compares a military ambuscade with a whale that strayed too close to shore, finding itself eventually trapped by a net.

Among the tosephot, a community of learned Jews in 12th/13th century France, it was discussed whether scaly, kosher fish found in the stomach of a whale - which is not a kosher animal - may be eaten by the abiding. From this it can be inferred that fish-eating, stranded rorqual whales were at the root of this academic religious debate.

The order of nature, or in Christian faith, of God's creation, had assigned whales the watery element. When whales left their assigned element, i.e. became stranded, the order of the godly creation was infringed upon. In Christian medieval and early modern thought, people did not seek to investigate the reason for this disorder, but rather attempted to interpret the meaning of this event within the framework of the godly plan for human salvation. Thus - in spite of the unexpected windfall of valuable commodities that could be manufactured from their blubber, meat, bones, baleen or teeth - stranded whales were interpreted as a harbinger of evil fate, as a portent of bad luck, or a mean omen. At any rate, they were events worth recording for future generations. Thus, from about the end of the European middle ages, stranding records start to become gradually more frequent.

Two large bones of whales that strayed into the Trave estuary, Baltic Sea, were suspended as a memorial outside Lubeck's ramparts in the 13th century. There is evidence for about 200 cases of whale bones hung in European churches, castles, and town halls - many of them now lost - which can be interpreted as "hierozoika", a Greek word designating items from the animal world hallowed by being mentioned in the bible. These bones mostly originated from stranded whales (a few from prehistoric, fewer still from large exotic animals), they were often interpreted as bones of the biblical giant Goliath or of Leviathan, and were sometimes traded long distances to be found hundreds of kilometers from the sea. Whale bones as "hierozoika" sanctioned political power of the church, feudal lords or municipal governments, and they were welcome diplomatic gifts between these institutions. In the country, landowners sometimes set up the paired jawbones of stranded baleen whales as arches in their gardens.

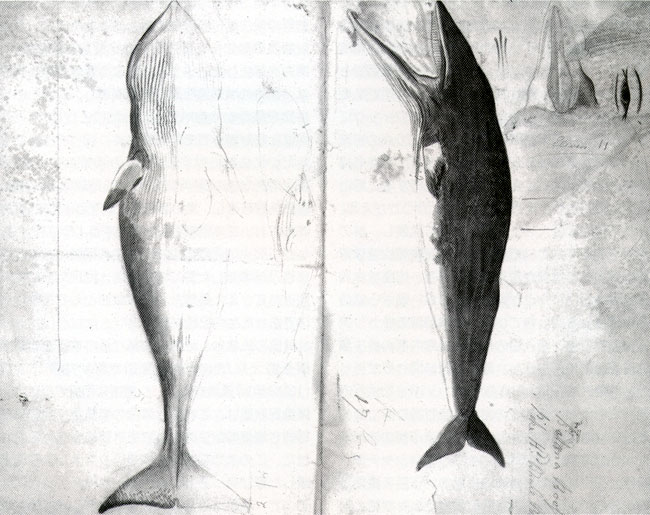

Another way of recording whale strandings for posterity was painting the huge "fish" for display in the same type of buildings, i.e. churches, castles or town halls. We know such commemorative, "public" paintings of stranded whales from the Mediterranean all around Europe to the Baltic Sea, frequently executed in a monumental format between the 1430s and the 1830s. Many of them have been lost. A noteworthy, surviving example is a life-size "portrait" of a minke whale stranded in the Weser estuary in 1669, painted by a student of Rembrandt on a 3.70 x 9.40 m canvas. For three centuries it had hung in the town hall of Bremen, was discarded in the 1960s, luckily retrieved and after restoration is now on display in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven (incidentally, the earliest realistic depiction of this species).

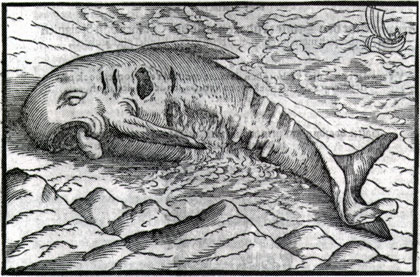

The spread of the letterpress, invented in the 1450s, brought about another potential for recording noteworthy events - such as whale strandings - or rather, disseminating the news of them to a larger clientele, who were willing to pay up to half a day's income for a printed broadside or pamphlet. Usually illustrated by a spectacular woodcut or engraving, a typeset text told the pertaining news story, often in quite a dramatic style, for mountabanks peddled these imprints by yelling the stories to an illiterate audience on marketplaces and fairgrounds. The oldest pamphlets on stranded whales known so far date from the 1530s. In medieval Christian tradition, they continue to interpret the "meaning" of a whale stranding, but gradually over the centuries, the prodigious aspects step behind more empiric ones.

Besides the "political profit" of displaying spectacularly big whale bones or huge commemorative paintings in public buildings, the commercial exhibition of entire mounted skeletons, of body parts in the flesh, or even entire carcasses of stranded whales, also has a long history in Europe. It started already in Antiquity. Bones from a whale stranded in present-day Israel were shipped to Rome to be set up for public edification by an organizer of circensic games in 58 BC. Another whale skeleton could be admired in 4th-century Carthage. In northern Europe, records of commercial exhibitions of whales set in in the 1450s. In 1549, duke Cosimo de Medici set up a sperm whale skeleton in a loggia of the Palazzo Vecchio of Florence (accompanied by a mural painting). The dried head and flukes of a sperm whale stranded near Antwerp in 1577 were transported on a cart over much of Flanders and Germany. Swiss entrepreneurs bought the skeleton of a fin whale stranded near Arles, France, in 1619. A unique broadside illustrates how the skeleton was set up in showrooms: the vertebrae were laid on two parallel poles, the ribs suspended perpendicularly, the jawbones laid on the floor, the skull hung by a pulley block from gallows or the ceiling, and the shoulder blades were mounted as a vertical tail fin. Town officials were sometimes bribed with souvenir bones from the whale, which explains the presence of "stray" whale vertebrae, ribs or flipper bones in town halls hundreds of kilometres from the sea, as well as decreasing measurements of the displayed skeleton in some updated editions of the pertaining broadside. Transport logistics having been solved early on, improved preservation methods brought about a real "boom" of commercial whale exhibitions in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some enterprizes had several whale carcasses on tour simultaneously, but these originated not from stranded animals, but from whales bought at whaling shore stations.

Besides differences, scholars of Japanese culture will recognize a few similarities between European and Japanese ways of dealing with stranded isana, the Great Fish. The humpback whales stranded at Shinagawa in 1798, e.g., inspired ukiyo-e artists and poets for two generations. Some whale shrines had torii made of whale jawbones. One ban-woodcut by Yoshitoshi shows a commercial exhibition of a rorqual whale at Fukugawa in 1875.

Following the recent paradigmatic change in contemporary western civilisation, whose dominantly metropolitan lifestyle has increasingly alienated it from nature, whale strandings now inspire a culture of public larmoyance. Awe and curiosity have given way to pity and a faddish environmental pessimism. Some western "whale huggers" even stricture children who - innocently seeking a little high ground above the adults - climb upon the carcass of a stranded whale! Such modern irrationality likewise is an expression of the perennial validity of the psychological archtype of the Great Fish. But unlike the irrationality of awe the Great Fish inspired in the past, permitting at the same time its material exploitation, the new western attitude is preemptive, dogmatic and intolerant.

1. Italian broadside on the stranding of a 13.5 m whale near Ancona, Italy, on 25 February 1602. Engraving, 22.1 x 33.1 cm. This broadside was possibly sold by the owners of a travelling exhibit featuring the skeleton of this whale. Barthelmess Whaling Collection, No. 846.

2. Fairly realistic woodcut illustration, 8.7 x 13.4 cm, of a half-rotten pilot whale washed ashore near Katwijk, Holland, on 20 September 1608. In the appertaining pamphlet the condition of the carcass is compared to a "rotting" peace treaty between the Netherlands and Spain. Barthelmess Whaling Collection, No. 241. This pamphlet and the previous broadside have been described in detail by Ingrid Faust, Klaus Barthelmess & Klaus Stopp: Zoologische Einblattdrucke und Flugschriften vor 1800. Vol. 4: Wale, Sirenen, Elefanten. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 2002, which comprehensively catalogues 145 European broadsides and pamphlets about whales stranded between 1531 and 1792 (in German; ISBN 3-7772-0205-3).)

3. Minke whale found floating dead on the Doggerbank, North Sea, on 9 January 1787. Pencil and watercolour drawing by James Sowerby (1757-1822), ca. 25 x 23 cm. After examination by scientists like John Hunter and Sowerby, the 17-foot carcass was commercially exhibited at the Lyceum, Strand, London, from 29 January till around the 12 February 1787. This drawing is probably the second oldest depiction of this whale species. The dorsal fin had been cut off. Barthelmess Whaling Collection, No. 709

Whaling in Korea and issues after the moratorium

1. Whaling culture in Korea

Regarding whaling along the coast of the Korean peninsula, whale bones have been excavated from the shell heap of Dongsam village in Busan in the New Stone Age. Further, since part of whale bones excavated from the shell heap of Suga village, Kimhae in Kyeong-nam Province, were observed to have been burned, it is conjectured that whale meat used to be eaten in those periods. In the rock engravings of Bankudae of Ulsan (National Treasure No. 285) that date back about 3000, there were drawings of marine mammals together with those of terrestrial animals such as tiger, wild boar, deer, dogs and sheep. Of the marine mammals, whales were found in the largest number. According to the research results later reproduced with computer graphics, it was found that, out of about 220 rock engravings discovered, 66 were those of marine mammals and 42 were those of whales. This shows that whales had been closely related to men at that time.

Now Ulsan has developed into a huge industrial complex, with no trace of ancient times. Originally, the Bay of Ulsan, located on the eastern coast of Korea, is a narrow and long bay with a deep recess. Its interior part had been known as a migratory route of whales from olden times, linked with the Taehwa River and the towhead of the estuary. Before the commercial whaling moratorium was enforced, whaling bases existed in Bang-ojin fishing port at the mouth of the Bay and Jang-seng-po fishing port inside the bay. Thus the relations of the area with whales have been very close. Bankudae is located a little over 10 kilometers from the mouth of Taehwa River, and it is considered that the sea had extended to that point in the olden times. As many as 42 rock drawings of fin whales, gray whales, sperm whales and killer whales have been found. Some of the gray whales were pregnant with calves. There are also valuable drawings in which people on board of the whaling boats were harvesting whales with harpoons and nets. These are valuable cultural heritage notable not only for the Korean history but also the world whaling history as a whole.

Subsequent introduction and the rise of Buddhism in Korea prevented the development of fisheries. Historical documents show that king's decrees were issued to prohibit killing of living things in Silla Kingdom in the year 15 under King Beob-heong (528) and Baekjea Kingdom in the first year under King Beob (599). Those decrees were applied not only to terrestrial animals but also aquatic animals, like whales, sea lions and fur seals. Fishing implements were destroyed by burning and fishing activities were banned. Such decrees first took a deep root in the mind of aristocrats, and practice of trading and eating those animals went out of existence. Fishermen found no motive for fishing and the Buddhist faith was gradually accepted in their lives. By the time ordinary people's religious life was dominated by the Buddhist thought, killing of animals came to be regarded as a sinful act and fishing activities as such were abandoned. As a result whaling in Korea also declined. But there remain historical records that show that even in those periods, stranded or drifted whales were of value as food for ordinary people and their oil as lamp oil for privileged aristocrats.

Buddhism flourished in Korea until the time the Koryo dynasty ended. The Korea succeeded by Choseon dynasty (1392) embraced Confucianism. Their policy to belittle fishermen because of extreme ideology of nobility and humble caused fisheries and whaling in Korea to survive only as negative and subsidiary means of subsistence. Because of this policy to give a very low esteem to fishermen, no reports of whale strandings were made to the government as all the profit was monopolized by the government officials. There are records that drifted whales were pushed back to the sea as unwanted guests.

. Advance of whaling by Big Powers to the Korean Peninsula

As the prohibition of killing animals by the Buddhist teaching and the thought to give low regards to fishermen under the Confucianism lasted more than 10 centuries, the whale stocks around the Korean Peninsula were kept in its unexploited state, but they were made target of whaling by the Big Powers of the world since around mid-18th century. The first whaling ships that appeared in the sea surrounding the Korean Peninsula were American whaling fleets harvesting fin and sperm whales from around 1848. Historical records show that the crew of American whaling ships sometimes landed on the Korean Peninsula without permission for procurement of food, water and charcoal, causing problems with the local residents. Subsequently, as the presence of abundance of whale stocks in the eastern coast of the Korean Peninsula was known, whaling ships came to the area, one after another, from Germany, France, Britain and Russia, making the Korean waters a competing ground among the Big Powers.

The Choseon dynasty then had been taking a policy to close itself to the outside world. These big powers shook the Korean government and the people at the end of this dynasty, with diplomatic pressures on the pretext of making lease negotiations to secure whaling bases of their own. The first lease treaty was concluded under quasi-compulsive pressures from Russia in March 1893, as a result of which it was decided that Russia would use, as its bases, Ulsan in Kyong-nam Province, Jan-Jeon in Kangwan Province and Mayang Island in Hamkyeng Province for 20 years. This gave a motive to British-Russian Whaling Union jointly established by the British and the Russians to launch whaling using part of Busan and Wonsan as their bases in December 1899, and to Japan to acquire whaling right within the territorial waters of Korea by obtaining whaling permit in February 1900. The "war" for whales between Japan and Russia was ended in Japan's favor as a result of Japan's victory in the Russo-Japan War started in 1904, and the whale resources along the Korean Peninsula came under Japan's monopoly.

3. Whaling under Japan's occupation

During the Japanese Occupation period which lasted 35 years from 1910 to the end of the World War II in 1945, Japan's fisheries capital made competitive advance to Korea and spread modern large-scale fisheries. Most of the fisheries with high profit and requiring large capital, such as engine-powered trawling, engine-powered purse-seine and large-type fixed net fisheries, and whaling, were managed by the Japanese. Statistics on whaling at the end of 1942 show that there were 17 whaling vessels with 242 workforce and harvest value of \1,661,892. Most of the whale meat was shipped to Japan. About 80% of all the catches were processed at the whaling bases of Jang-seng-po and Bang-ojin fishing ports in Ulsan on the eastern coast and the remaining 20% were processed at Hoksan Island in Jeon-nam Province and Oechong Island in Chang-nam Province on the western coast.

Regarding the Japanese whaling vessels which had operated to the end of the war, the U.S. military authorities declared that all the fishing rights before August 9, 1945, should be made invalid, and all the vessels and equipment related to such activities should be confiscated. Nevertheless, the Japanese shipowners returned all the vessels to Japan with their families, furniture and other properties amid the postwar confusion.

4. Korean War and restoration of whaling

As stated earlier, all the whaling vessels, managed by the Japanese, had been withdrawn to Japan, and no whaling vessel was left in Korea after liberation. Only whaling bases and experienced whaling ship crew and flensers were left out. Those people having whaling skills were willing to resume whaling based on whaling technique they had learned from the Japanese. As a result, they established "Choseon Whaling Co." in Busan and Ulsan in September 1946, purchased two small restructured whaling boats from Japan, and started operation. The catch in the first whaling season was favorable with 65 fin whales, enabling them to establish their initial business base. Subsequently, the number of whaling vessels, including small boats, increased to 18 after the establishment of such companies as Daedong Whaling Co. and Tong-yang Whaling Co. However, after the liberation, they were unable to export whale meat to Japan, and due to long religious habit of not eating whale meat in Korea, the prices of whale meat remained low, causing difficulty in maintain the enterprise. The 6.25 Korean War, which erupted on June 25, 1950 by North Korea, was a tragic war for the Korean people. But, fortunately to the whaling industry, consumption of low-priced and readily available whale meat increased to solve the issue of protein supply especially to counter the food shortage in the wake of the inflow of over 3 million refugees southward to small tract of areas in the east side of Nactong river such as Taegu and Busan. The increase in demand pushed up the price of whale meat, helping the Korean whaling industry to thrive anew. The normalization of relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 1966 enabled resumption of whale meat exports to Japan, causing whaling to become a thriving industry. Before the IWC's commercial whaling moratorium came into force in 1985, a total of 21 whaling vessels (total permitted tonnage: 1,389 tons) caught an average of 625 whales equivalent to 1,774 tons a year in 1980-1984. The industry earned $3.54 million dollars of foreign exchange by exporting an annual average of 846 tons of whale meat to Japan during the period.

5. Moratorium and the end to whaling

When, at the 34th annual meeting in 1982, the IWC resolved to prohibit commercial whaling, the Korea, together with Japan, protested to the IWC's decision but was forced to abandon whaling under pressures from the United States that "it would reduce to zero the allocation of pollock in the U.S. waters to any country diminishing the effectiveness of the IWC's regulations." The amount of pollock the Korean North Pacific trawling vessels had been catching in the Bering Sea for 1981-1985 totaled 296,000 tons on the yearly average, while the catch of whales was 1,774 tons. In a bid to secure overall fisheries profit, Korea abandoned whaling. Japan lodged a formal objection to the IWC's decision, paving way for future research whaling and small-type whaling. On the other hand, the Korean government did not file an objection. Whalers also abandoned their whaling permit, allured by the compensation for whaling rights and the fund to transfer to other types of fisheries, as proposed by the government. Later, the government took further unwise measures to delete clauses related to whaling in the revised Fisheries Law.

6. Efforts to resume whaling and issues surrounding it

Overall prohibition of whaling remains in force for 17 years after the commercial whaling moratorium was enforced. In the meantime, whale resources along the coast of Korea have increased dramatically. According to the surveys by the National Fisheries Research & Development Institute, it is estimated that more than 110,000 heads of 35 species of cetaceans are found migrating in the area. Those increased cetaceans prey on important fish species harvested by fisheries, such as squid, saury, mackerel, sardine and pollock. Fishermen are now protesting because their catch is decreasing because of predation by cetaceans. As evidence of increase of whale population, there are an increasing number of incidental catches of whales in fishing nets year by year. Within the marine police district of Pohang on the eastern coast only, the whale incidental catches have been increasing annually from 45 whales in 1999 to 95 in 2000, 143 in 2001 and 65 as of the end of July 2002. Given the fact that most of the whales caught incidentally were minke whales, fishermen are demanding for appropriate culling of whales because of abnormal increase of whale resources affect the fishery resources and the livelihood of fishermen. They also call for sustainable use of whale resources. However, the problem here is that, 18 years after the termination of whaling, there remains no single whaling vessel, and whaling gunners are all in their seventies and no landing stations are left. Further, there has been no adequate research on whales because of an insufficient number of whale researchers. In closing, I wish to express my expectation for cooperation from the Japanese people for the solution of these issues.

Performance at the Ulsan Whale Festival,reproducing ancient whaling in Korea.

Children of Arikawa-cho,Nagasaki Prefecture,making presentation of "Hazashi Daiko" (Hazashi Drum Performance), a traditional whale-related performing art in japan,at the Ulsan Whale Festival(May 30,2003)

Japanese community participated in the festival from last year. Test eating of whale dishes cooked on the spot,using whales caught incidentally locally,was popular among visitors.

Homage to Late Mr. Akiyama and Expectation for Prof. Koizumi

Fisheries Journalist

Secretary of the Group to Preserve

Whale Diet Culture

Descendent of the Founder of Boshu Whaling

We received the sad news of the sudden death on January 16, 2003 of Mr. Shotaro Akiyama, an influential photographer in Japan. He collapsed with a heart attack during the judging of a photo prize contest.

Mr. Akiyama had many titles, but unique among them was that of Chairman of the Group to Preserve the Whale Diet Culture. He was elected head of this Group when it was founded on November 27, 1987.

The Group was formed by opinion leaders and owners of whale food restaurants throughout Japan. Among the notable members are Hayashiya Kikuzo (traditional comic story teller), Chizuko Togaeri (essayist), Sanae Sato (novelist), James Miki (playwright), Takashi Atoda (novelist), Chue Takubo (Professor of Kyorin University), Takeo Koizumi (Professor of Tokyo Agriculture University) and Rempei Komatsu (former editor of Asahi Newspaper). I was appointed Secretary of the Group because I had more time available for the management of the Group than other members.

Mr. Akiyama was elected chairman by the consensus of the members. Everyone knows that he was a gourmet deeply versed in various types of cuisines, and above all, an ardent lover of whale dishes. In 1982, when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) passed a commercial whaling moratorium, Mr. Akiyama wrote an essay titled "Let us eat whale meat" in the Sankei Sports Newspaper. In that essay he deplored the event: "Nothing is more delicious than sushi with whale prime meat. I feel anger if I am forbidden to eat that delicacy. It is truly regrettable that there are people who are insensitive to the serious consequences of intervening in the food culture of other people."

As Secretary, I visited Mr. Akiyama's office in Roppongi, Tokyo, to ask him to become chairman of the Group. He accepted our request instantly, saying: "I will become chairman if we can continue eating whale food." Shortly afterwards, he confessed that his ancestors were the Daigo Family that started whaling in Boshu (now Chiba Prefecture near Tokyo). "That's why I get excited when it comes to whales," he added.

This was a surprise to me. The Daigo Family, which was Mr. Akiyama's maternal ancestry, began the harpoon-type harvesting of Baird-beaked whales from a base in Katsuyama (now Kyonancho) in 1612, and was granted a monopoly right for whaling from the local daimyo. "While I was a student, I was very happy to go home during summer vacation. I ate whale meat every day to gain strength," said Mr. Akiyama.

On November 27, 1987, the first meeting of the Group to Preserve Whale Diet Culture was held at Taruichi, a restaurant specializing in whale food in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Some 120 people attended. The nationwide Yomiuri Newspaper reported upon Mr. Akiyama in the next day's column, entitled "Face." He told the Yomiuri: "I cannot accept the assertion that we should not eat even a slice of whale meat. Some species of whales are increasing. Whether you take protein from cattle or whales is a matter of cultural preference. I was set up as chairman of the Group to Preserve Whale Diet Culture because I am so fond of eating whale meat. It is my belief that whaling should be allowed as long as the stock is kept from depletion."

At the funeral of Mr. Akiyama on March 5, about 2,000 people came to pay respect to him.

A Patriot who fights for whaling cause

As successor to Mr. Akiyama, Professor Takeo Koizumi of the Tokyo Agriculture University stood out as the primary candidate. After sounding out the views of the major members, the consensus was to elect him as new chairman. When Mr. Takashi Sato, vice chairman of the Group and owner of Taruichi Restaurant, and I met with Prof. Koizumi, we could not get an immediate affirmative reply from him. But on the next day, I received a fax from him that said he would agree to assuming the post and will do his best once appointed to it.

Prof. Koizumi was born in 1943 in a sake brewing family in Fukushima Prefecture, northern Japan. He teaches zymology at the Tokyo Agriculture University. He is not only a scholar but an essayist, a researcher of diet culture, and a writer. He is author of about 100 books, including those written in collaboration with others. His representative works include "Episodes of Sake," "Heisei Health Lessons," "The Pleasure of Natto," "Strange and Queer Foods," "Traveling China in Search of Strange Foods," and "Degraded Food Life and the Japanese."

In his recommendation on "Degraded Food Life and the Japanese," Rokusuke Ei, a multi-talented commentator, described Prof. Koizumi as a "patriot with chopsticks." Reading this book you may find that this observation is accurate. In the book, Prof. Koizumi deplores the probability that the Japanese spirit will naturally become reduced when you see the low food self-sufficiency rate, young people moving from traditional Japanese food to western style fast food, and young housewives buying ready-made foods at supermarkets without bothering to cook by themselves. On the whaling issue, he shrewdly points to the sheer absence of justice in the assertion of anti-whaling proponents and stresses that it is the wisdom of mankind to increase fishery resources by culling whale resources.

At a party to celebrate Prof. Koizumi's chairmanship on April 7, he said that once he becomes chairman he will stage a campaign to attract public attention to the whaling issue by first targeting appeals to women and mobilizing the mass media. He will tackle the whaling issue with a commitment to save the Japanese people. This patriot seems to have in mind to hold in check the further degradation of Japanese food life by first

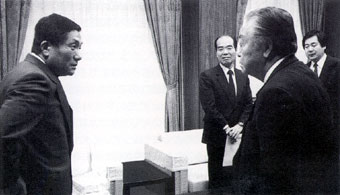

The late Mr.Akiyama making a petition to Minister of Agriculture,Forestry and Fisheries Takashi Sato for continuation of whaling.At the extreme right is Dr.Takeo Koizumi.The author is in the center.(December 1987)