- WHAT WAS ACHIEVED AT THE SHIMONOSEKI IWC MEETING

・Double Standard of the U.S. Exposed.

・Science Base position of Japan gained one step further.Masayuki Komatsu

Director, Resources and Environment Research Division Fisheries Agency of Japan /

Alternate Commissioner of the Government of Japan to the International Whaling Commission - SHIMONOSEKI AND THE IWC

Kiyoshi Ejima

Mayor / City of Shimonoseki - WHALE-HUGGERS' CASE IS UP THE SPOUT

From Sydney Morning Herald Dated 28 May 2002Padraic P. McGuinness

Journalist - GLOBALISM AND THE WHALING ISSUE

Takao Hosokawa

Professor / Agriculture Department / Ehime University - EATING IS BELIEVING - WHALE DIET CULTURE EXPERIENCE SEMINAR

"Let's eat whale meat and think about the whaling issue"Hisashi Hamaguchi

Associate Professor / Sonoda Women's College - Photo Library

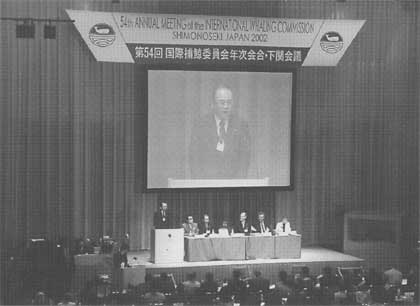

The 54th IWC Meeting in Shimonoseki

ISANA Dec. 2002 No.26

index

ISANA Dec. 2002 No.26

WHAT WAS ACHIEVED AT THE SHIMONOSEKI IWC MEETING

Double Standard of the U.S. Exposed

Science Base position of Japan gained one step further

Director, Resources and Environment Research Division Fisheries Agency of Japan

Alternate Commissioner of the Government of Japan to the International Whaling Commission

This year, just 20 years after the commercial whaling moratorium was adopted, the 54th Annual Meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was held in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, western Japan--the first such meeting in Japan after the Kyoto meeting nine years ago. As this meeting was held in Japan and was widely reported daily by the televisions and newspapers, you may probably know the results of the meeting. In this report, I would like to highlight some of the latent achievements of the meeting that had not been covered by the media.

U.S. Double Standard widely exposed

One of the points deserving attention from this annual meeting is that the proposed extension of the Aboriginal Subsistence quota for bowhead whales, jointly proposed by the United States and Russia, was turned down. This proposal requested the IWC to grant a quota of 280 bowhead whales for the period from 2003 to 2007 for Inuits in Alaska in the United States and aboriginal people in the Chukotka Autonomous District in Russia. Up to the present, the same proposal has been unconditionally approved for a five-year term. However, it was put to a vote this time, and was denied with the opposition of 14 countries, including Japan. Although Japan gave support, as it did previously, to the needs of aboriginal subsistence whaling as a matter of principle, it asserted that the quota should be requested on a year-to-year basis in view of the current fragile and unknown state of the bowhead population.

The bowhead whale is even now classified as a Protected Stock by the IWC Scientific Committee, with its population level ranging from 7,000 to 9,000. When the Catch Limit Algorism:quota calculation procedure for commercial whaling, commonly known as the Revised Management Procedure (RMP), is applied, the catch quota for this species should be zero for the coming 30 years. On the other hand, while supporting whaling by its aboriginal people despite the state of the population, the United States has stood firmly opposed to the Japanese request for an interim quota of 50 minke whales for coastal whaling communities. The population status of this stock is robust and healthy, with modestly at least 25,000 individuals estimated to be living in the near-shore area of Japan. The countries opposed to the extension of the quota for bowhead whales harshly criticized the double standard of the United States. Through a process of discussion over the aboriginal subsistence quota renewal at Shimonoseki meeting, the United States ended up in exposing its double standard broadly.

Balance of power closed due to increase in member States

At this annual meeting, six countries (Benin, Gabon, Mongolia, Palau, Portugal and San Marino) joined the IWC as new members, bringing the total number of members to 49, including Iceland, which rejoined the Commission last year but was treated as an observer by undue treatment of anti-whaling members. Along with the increase in members, the countries concurring with the Japanese position also increased steadily, giving a bright sign for improvement of the present anomalous state of the Commission. As for Japan's request for an interim quota for the coastal whaling communities, which Japan has been presenting annually, the voting result was short of a simple majority only by a small margin, with 20 in support and 21 against. Of course, a three-fourth majority vote is required for an amendment of the IWC Schedule, but the voting results showed remarkable progress as compared with 10 years ago when I first joined the Japanese delegation to the IWC. At that time, out of 39 members, only 5 countries, including Japan, supported the promotion of whaling.

In face of this changing situation, the anti-whaling bloc is criticizing Japan for buying the votes of developing countries in exchange for its Official Development Aid (ODA). But Japan is now extending ODA to more than 150 countries, among them being anti-whaling countries, such as India, Brazil, Mexico and Kenya. The reason for the increase in the number of supporting countries for the cause of Japan is that Japan's position based on scientific evidence has been accepted internationally.

Further, the Commission agreed at this meeting to introduce a 3-year provisional measure to alleviate the membership contributions of developing countries in its review of the current IWC contribution system. As a consequence, it is expected that the IWC membership of developing countries sharing position on the sustainable use of marine living resources will be further promoted. The reasons for this expectation are twofold: the fact that the large amount of fish consumed by whales came to light by Japan's research efforts; and, the fact that the issue of whales is an issue of fisheries that should be recognized even by countries that do not engage in whaling as long as they are coastal and fishery-engaging states.

No resolution calling for restraint of Japan's research was adopted.

--U.S. loses strong ground for certification under the Pelly Amendment--

For the first time since Japan started its research whaling program in 1987, no resolution calling for the reconsideration or refrainment of Japan's research programs was adopted--which was in clear contrast to the annual adoption of such resolutions until the last meeting. These simple-majority resolutions, which are in essence a violation of the provisions of the Convention, have no effect on the research programs, but anti-whaling nations based politically the negative anti-Japanese publicity. Japan's research programs are legal activities fully in compliance with Article 8 of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. The major reason for non-adoption this time was because the meeting was often thrown into confusion due to prolonged debate on the issue of the extension of the aboriginal subsistence whaling quota. Whatever the reason, it is to the advantage that a resolution urging to refrain from its research programs, which had passed continuously in the past, was not adopted.

Although, seen superficially, no substantial progress was observed at this annual meeting, with resumption of whaling postponed, it is certain that our position is steadily taking root in the Commission's debate.

Mr.Komatsu surrounded by reporters outside the meeting room.

SHIMONOSEKI AND THE IWC

Mayor

City of Shimonoseki

The 54th Annual Meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was held in Shimonoseki from April 25 to May 24, 2002.

In 2000 at the 52nd Meeting in Adelaide, Shimonoseki was selected as the venue for the 2002 IWC meeting, after competition for sponsorship with New Zealand. At the London meeting last year, I made a welcome speech for the meeting in Shimonoseki, and since then I concentrated my efforts on making the meeting a success.

As this international conference was scheduled for about a month with up to 500 visitors, both municipal government employees and the citizens wished to entertain our guests heartily under the slogan "Welcome to Shimonoseki."

As a first step, the Council for Promotion of the IWC Meeting in Shimonoseki, a nationwide organization, was established on August 23, 2001. In October the same year, the IWC Meeting Promotion Section, executive office headed by myself, was set up in the Municipal Office, and in November, a steering committee was organized centering on citizen groups. In this way, full-scale preparations for the meeting were set in motion.

Because of a large number of foreign participants in the IWC meeting, we publicly recruited 150 language volunteers to assist foreign visitors at the Kaikyo Messe Shimonoseki Conference Hall, hotels and train stations. To our very delighted surprise, over 300 volunteers applied, far more than we expected. I felt very confident to see the presence of so many citizens who have internationally-oriented minds.

We had contributions from various people in realizing a Shimonoseki-style welcome under the joint cooperation of the Municipal Office and our citizens. Volunteer efforts included the removal of illegal advertisement boards and posters from around the Conference Hall. Various types of training sessions were held for accommodating guests by hotels, inns, restaurant business, taxi companies, and IWC meeting ad wrapped bus operations and for preparing announcements in English for transportation. And a whale-shaped topiary decorated with ivy and flowers was set up at the Strait Dream Plaza just in front of the Conference Hall.

Thanks to the cooperation of many of our citizens, I am honored to report here that we had words of appreciation from delegates of various countries on the last day of the meeting. Especially to be noted was the remark by the delegate of Germany, the host of the 2003 IWC meeting, who said "We may not be able to entertain delegates as Shimonoseki people did, but we will do our best on the example of the Shimonoseki meeting." Such encouraging words certainly helped to dissipate the painstaking efforts by the Shimonoseki Municipal officials, volunteers and all the people of Shimonoseki in leading this memorable event to a success. I would like to take advantage of this article to express my heartfelt gratitude to all the citizens of Shimonoseki and people who cooperated for their dedicated contributions.

Shimonoseki has been deeply related to whales from ancient times. Whale bones have been excavated from the Ayaragigo Remains, designated as a valuable historical site. Monuments dedicated to Oka Juro and Yamada Tosaku, two unforgettable figures who initiated modern whaling in Japan at the end of the Meiji Era (1868-1912), have been built in Hiyoriyama Park in the city, showing that the city has been closely involved in the initiation of modern whaling.

In the first decade of the Showa Era (1926-1983), the Taiyo Fishery Co. led by Nakabe Ikujiro (Now Maruha Corporation) thrived during the Antarctic Whaling Period. Needless to say, Shimonoseki is the place of origin of the Japanese Antarctic whaling.

Mayor Ejima addressing the opening ceremony

TWHALE-HUGGERS' CASE IS UP THE SPOUT

From Sydney Morning Herald Dated 28 May 2002

Professor Emeritus

Pukyong National University

The meetings of the International Whaling Commission have long been noted for unproductive brawling. The only difference at the most recent one was that Japan is finally resisting being pushed around by the whale-huggers of the rest of the world.

In the process it exposed the absurdity, indeed the hypocrisy, of the Australian Government's commitment to a South Pacific whale sanctuary.

The IWC was set up originally as a result of well-justified fears that major whale species were in danger of extinction as a result of over-fishing. This danger is long past.While there is reason for caution and the maintenance of bans on fishing for some species, in general there is no longer any good case to be made against whaling to supply those people who wish to eat whale meat. It is true that no-one needs to eat whale meat these days, any more than anyone needs to eat pork - but that is no reason to ban its consumption.

It is also true that not a single indigenous person of any country, including the United States or Russia, needs to eat whale meat.

Japan acted perfectly logically in insisting that if there were to be a ban on whaling it should apply equally to those who, in the name of some special sacred right of indigenous peoples, had been exempted from the general ban. Their protein needs can be perfectly adequately supplied in other ways - they simply do not depend for their survival on eating whales.

If its claim is to be based on tradition, then Japan has an equally valid claim to hunt and eat whales on a traditional basis. If the survival of a whale species is not threatened - and it is getting harder and harder to argue with a straight face that minke whales, which are very numerous in the Southern Ocean, would have their survival threatened by limited commercial whaling - there is no sense in protecting it.

Japan already conducts some whaling, under the guise of scientific study, and it is ridiculous to suggest that this in any way threatens the survival of the minke.

Where does the obsession with preventing whaling spring from? Once the rational aim of ensuring the survival of species has been achieved, the rest is just a hotchpotch of emotion and superstition. Of course whales are remarkable beasts, but so are pigs - and no less intelligent. What makes whales morally superior to pigs? It is just that they are bigger?

There simply is no good reason to refrain from killing and eating whales unless one is a vegetarian, and that is a personal not a political choice. Some humanitarian considerations are involved but they are not the main point.

Few opponents of whaling will allow that any improvements in technique or any degree of certainty about species survival would permit a resumption of commercial whaling.

The real mystery is why the Australian Government wastes so much diplomatic effort on this nonsense. It is understandable that Labor governments like to throw the odd bone to their own lunatic fringe supporters, but it can only be supposed that the Coalition has itself a sufficient fringe of such supporters to feel it necessary to do the same.

There is no international political capital to be gained from the continuation of the anti-whaling charade, nor the South Pacific sanctuary proposal. It must be that much of the push for the sanctuary comes from bureaucrats, who are disproportionately influenced by the fashions of the half-educated middle classes.

It may be that Japan has finally decided to force the collapse of the nonfunctional IWC. It has successfully persuaded a number of other countries to agree with it. Whether this has involved payments, direct or indirect, hardly matters - it is standard practice in world politics for wealthy countries to bribe poor countries (unfortunately, most of the money goes to the privileged classes, not to relieving poverty).

The lies and misrepresentations peddled by secretive non-government organizations such as Greenpeace are understandable. Campaigning against whaling is one of their best money-raisers.

There is certainly considerable feeling in the community against whaling. But that is easily dealt with on a domestic level - few people in Australia would feel moved to campaign for a resumption of Australian-based whaling, which had a proud history.

But why should Australia, the moralisers of the European Union and other comfortable rich countries try to impose their dietary and religious preferences on the rest of the world?

Opening ceremony of the 54th IWC meeting in Shimonoseki

GLOBALISM AND THE WHALING ISSUE

Professor

Agriculture Department

Ehime University

More than a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union that had led the socialistic bloc in the world, the United States, the champion of capitalism that stood in stark confrontation with socialism, further reinforced its confidence and has been expanding its influence, imposing its patterns of action on other countries. The Soviet breakdown meant the collapse of the socialistic ideology as a norm. It also meant that the Soviet politics were engulfed by its old antagonist, the United States, in the wave of globalization. The United States globalized information through its powerful information transmission capability. In other words, it spread in the world the American tenet that unregulated free economy is good. Thus, the United States succeeded in globalizing the politics of the Socialist countries.

There may be diverse interpretations of the word globalism, but the point here is that globalism entails the imposition of value systems. It implies that countries and regions having their own traditional rules and customs should abandon them and comply with the global rules.

The autonomy of whaling rooted in regions, it seems to me, has been utterly deprived under the pretext of environmentalism, which is a form of globalism. There is a stronger tendency to make light of what has been rooted in a certain region or climate under the name of unilateral globalism. Amidst such circumstances, agriculture, forestry and fisheries having strong roots in the regions and climate of Japan are forced to suffer decline, and whaling is no exception.

In the present situation formed by an international framework under the leadership of the United States (i.e., the commercial whaling moratorium), the traditional whaling communities that were deprived of their right to a livelihood are agonizing in search for their regional identity. In December last year, the present author visited Ayukawa in Miyagi Prefecture and Abashiri in Hokkaido--two of those communities--and learned from people involved in whaling about the difficult situation in which they had been placed, including the problem of finding successors for their jobs.

Mr. B of the whaling company A in Oshika Town of Miyagi Prefecture told me about the successor problem as follows: "We are urging the Fisheries Agency for the resumption of whaling because we, who lived on whales, do not want to see whaling disappear in our generation. Our company fortunately has two staffers in their twenties, while the other two are in their fifties and one in his sixties. So we have a balanced staff structure in terms of age. But we cannot recruit younger people if there is no future prospect for whaling. Especially, we face the need to train new whale flensing staff. At present, the oldest flenser is 75 years old. Flensing requires many years of experience." Mr. C, a staff of the Institute of Cetacean Research in Ayukawa, Oshika Town, said "there was no government compensation for the people engaged in whaling after the enforcement of the commercial whaling moratorium. Those who lost jobs sought means of livelihood in other sectors such as manufacturing and construction. Even if commercial whaling is resumed, it would be difficult to employ young people in whaling because of technical reasons."

Mr. C pointed out the following needs to preserve whaling culture. "After Maruha Corporation pulled out from Ayukawa, the vacated land was turned into Whale Land, a tourist spot, but this facility is now running deficits. Visitors increased after the entrance fee was reduced from 1,000 to 700 yen but still the deficits remain. The town cannot close Whale Land because it is necessary to preserve the whale culture. The traditional whale festival is held once a year to keep our whaling culture, but, in reality, the number of people not interested in whales is increasing. Whale meat is served for school lunch once a month, with the aim to have the younger generation know the taste of whale meat. I hope that more young people will come to eat whale meat. Previously, you had never paid for whale meat. It had been given as a gift. In other words, sharing had been practiced so commonly. As a matter of fact, sharing of whale meat constituted the symbol of this community."

Mr. E of the whaling company D of Abashiri, Hokkaido, recounted that whale dishes formed traditional family cuisine there. "People in Abashiri do not eat frozen whale meat because they had been used to eating it raw. Now the whale meat supplied is only that from research whaling. They waited until the next spring as they wanted fresh whale meat. We don't have the habit of eating hari-hari nabe (whale meat boiled with vegetables). We cooked fresh meat as steak, or fried with ginger and bean paste (miso). As people do not have refrigerators they used to preserve whale meat in soy sauce. The period when the whale meat was supplied was from April to June. And after they had eaten up their share, they did not eat whale meat until next spring. There had been no restaurants specializing in whale dishes because whales had been cooked at home. Recently, a whale restaurant opened in this city and seems to be attracting tourists. But for people in Abashiri, whale was something to be eaten at home. As a matter of fact, whale was the only meat available. It was an inexpensive daily foodstuff."

Mr. G of a marine product processing company F in Abashiri, expressed his dissatisfaction about the International Whaling Commission as follows: "At present the IWC does not recognize subsistence whaling in Japan. We hope coastal whaling in Japan, including that in Ayukawa, is recognized as subsistence whaling. In other words, we want that coastal whaling in Japan will be treated in the same way as subsistence whaling by Inuits in the United States. We want the IWC to recognize a provisional quota of 50 minke whales in order to bring relief to whaling in our region."

"I am not so much concerned about the issue of whale flensing techniques," he continued, "but it would be more difficult to recruit gunners and crew. This problem should be solved the soonest possible. I am now planning to organize a whaling campaign in the festival of Abashiri. I also intend to attend the annual meeting of the IWC meeting in Shimonoseki. It is my expectation that Japan's proposal on the resumption of commercial whaling will see one step forward to its realization at the coming IWC meeting," he said.

This time I visited Ayukawa and Abashiri, two of the traditional whaling communities in Japan, and interviewed people involved in whaling. After the visits, I confirmed that those people, including municipal government officials, are making efforts not to terminate whaling tradition. However, what is more important in preserving whaling and whaling culture would be to build up a network of the whaling communities' activities and transmit the information to the world as Japan's campaign for the resumption of whaling.

The present trend towards globalism represents the unilateral "imposition of rules and value judgments" by the United States. A commercial whaling moratorium is in place and the right of livelihood by traditional whaling communities has been infringed upon by environmental globalism that has made the whale a symbol of environmental protection under the slogan that "the earth's environment cannot be preserved if we cannot protect whales." This situation which is now before us clearly represents the negative aspect of globalism. Japan needs to fight back the U.S.-led universalism under the name of "globalism" that denies regional traditions and customs. There is indeed a need to correct the present abnormal situation of the IWC--an international framework for whaling dominated by environmental globalism that gives little regard to the will of whaling communities.

EATING IS BELIEVING - WHALE DIET CULTURE EXPERIENCE SEMINAR

"Let's eat whale meat and think about the whaling issue"

Associate Professor,

Sonoda Women's College

Since the academic year 1995, the present writer has been teaching a course on the whaling cultures of various places of the world to students specializing in international food culture at Sonoda Women's College. According to a questionnaire carried out in the classroom, the ratio of new students having the experience of eating whale cuisine showed a gradual decline from 79% in 1996 to 67% in 1997, 68% in 1998, 58% in 1999, 43% in 2000 and 41% in 2001. It has been a long time since whale cuisine disappeared from school lunches and the tables of ordinary households. Considering this phenomenon, the experience of young people eating whale will continue to decrease in the years ahead.

My college carried out a whale cooking and eating seminar in 1995 with whale meat supplied from the Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture (See Isana No. 14). In recent years, a number of students expressed to me the hope to eat whale meat. Based on my experience in the classroom, young women still consider whales as food while they also regard them as objects of observation and amusement. I thought it possible to hand down the whale diet culture if whale food is served when the young people feel like eating it.

It is against this background that the Whale Diet Culture Experience Seminar took place on December 9, 2001, with a supply of whale meat and other products from the specimens taken in Japan's 2nd-Phase Northwestern Pacific Whale Research Catch Program in 2001 by the Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR). During this seminar, the second-year students specializing in international food culture demonstrated the cooking of whale products in the morning as part of the class activities. Other students and invited guests took part in a trial eating session of prepared foods at lunchtime. In the afternoon, students attended a lecture under the theme of "Whales and Whaling" by Mr. Kazuo Yamamura, a Board member of the ICR. A total of 130 people participated in the eating session, including students from China and Korea, and 80 students attended the lecture session. That means some attended only the eating session, but it must have served half the purpose of this undertaking.

After the lecture, a simple questionnaire was made among the participants. It first asked the students whether they had eaten whale meat before. Students were then asked to assess the six items of whale cuisine served in the eating session under the five categories of (1) very tasty, (2) tasty, (3) neither good nor bad, (4) not so tasty, and (5) not tasty at all. The six items served were sashimi (raw whale meat), tatsuta-age (fried whale meat), harihari-nabe (whale meat boiled with vegetables), shigure-ni (whale meat cooked in soy sauce), bacon and whale meat soup. A total of 69 students responded to the questionnaire.

Regarding the experience of eating whale meat, 48% responded yes as against 52% who replied no. Probably because some people of advanced age, such as parents and college employees, were among the respondents, the results exceeded 41%--the figure of a similar questionnaire conducted only on new students at the start of the school year. The results showed that slightly over half of the respondents ate whale meat for the first time. What follows are their impressions of their first encounter with whale meat.

If we consider "Very tasty" and "Tasty" combined as a favorable assessment and "Not so tasty" and "Not tasty at all" as an unfavorable assessment, tatsuta-age topped the list with a favorable assessment of 85%, followed by harihari-nabe and sashimi with 48% each and bacon with 39%. From this we can conclude that the support rate for whale dishes is high among young women. This reflects the tendency of young women to favor fried food and refrain from too greasy food such as bacon.

One unexpected result was the high evaluation of the whale soup. It should have tasted greasy because whale blubber is used. But the fat and lye must have been removed well. On the other hand, the taste of the harihari-nabe sauce was a little thin- a probable cause of the lower evaluation. It is difficult to cook strictly according to a recipe when you cook for over 100 people. Also it was a student trial, and they could learn from failure. This should be left for future practice.

What follows are some general comments by the students.

"I imagined that whale meat was hard. But this perception disappeared by today's experience. Especially, I found sashimi very easy to eat because it was not hard and smelly. It tasted like tuna red meat."

"Whale dishes tasted half fish and half meat. I found harihari-nabe and whale soup a bit smelly. I found tatsuta-age tasty."

"After eating various whale dishes, I thought tatsuta-age and shigure-ni suit the Japanese taste. I consider whaling is an important culture. Now I am not against whaling."

The present author makes it a rule to lecture about whaling culture and whale diet culture for a semester of every school year. I found it difficult to have students with no experience of eating whale food to appreciate the importance of whaling culture. Because of anti-whaling publicity through the media, at times questions arose as to whether or not whale is a food. But, after eating, students came to be convinced that whale is a food. Truly, eating is believing.

Fortunately, my college has cooking facilities, and cooking lessons are being given to students. It is the wish of the present author that he will make the best use of this learning environment and continue to study more about whaling culture and whale diet culture. (Of course, over a table of whale dishes at times.)

Questionnaire regarding the sampling of whale dishes (N=69)

| Very tasty | Tasty | Not good nor bad | Not so tasty | Not tasty at all | |

| Tatsuta-age | 26% | 59% | 15% | - | - |

| 85% | - | ||||

| Shigure-ni | 38% | 41% | 18% | 3% | - |

| 79% | 3% | ||||

| Whale soup | 27% | 52% | 17% | 2% | 2% |

| 79% | 4% | ||||

| Sashimi | 24% | 24% | 40% | 6% | 6% |

| 48% | 12% | ||||

| Harihari-nabe | 8% | 40% | 34% | 10% | 8% |

| 48% | 18% | ||||

| Bacon | 11% | 28% | 25% | 14% | 22% |

| 39% | 36% | ||||

College students cooking harihari-nabe during the seminar

THERE EXISTED A MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE GRAY WHALE IN THE WEST COAST OF THE JAPANESE ARCHIPELAGO

Biologist

The IWC and its members seem to have done the impossible once again. Namely, to speak out of both sides of their collective mouths at the same time.

The IWC refuses to apply one rule collectively. It seems vastly unfair and undemocratic to allow the native peoples of one culture to continue in the taking of cetacean species for food sources while refusing to allow other cultures to do the same. To argue that it is agreeable to allow Native Americans and Inuits to hunt because it is part of their heritage and culture, while ignoring the histories of Icelandic, Norwegian, and Japanese communities borders on political favoritism. In this day of dwindling food supplies, rising food costs, and rampant hunger in many parts of the world, it seems negligent to ignore the bounty that the sea might bestow upon us.

As distasteful as it might be to those with other means, the quantity of available food that the harvest of one minke whale allows could mean the difference between sustenance and starvation to a variety of native peoples. The industry of whaling alone assures the continued financial support of thousands that might have few other resources. The self-imposed limits that many countries have set upon the taking of endangered cetacean species allows that they are concerned and sensitive to effect of unrestricted or unregulated commercial whaling.

It would seem that the IWC could make better use of it's time by acknowledging the fact that any country interested in being a member of it's organization already understands the importance of the IWCfs mission. No organization succeeds by alienating it's members or possible allies.

We do not condemn the Hindu practice of refraining to slaughter cattle even though vast numbers of people could avoid starvation in countries that foster such beliefs. How then, does it make any sense to condemn countries that seek to sustain their people by continuing traditions that go back for dozens of generations? Surely, the ability to feed and sustain onefs family and community ranks the highest on anyonefs list of priorities.

While I would be among the first to look for other means of food production and financial independence, I could not in good conscience allow humans to suffer for want of practical application of natural resources. I honestly believe that some kind of median is possible while protecting the rights of all concerned.

As a scientist, I have watched while millions of dollars have been spent on the unsuccessful attempt to rehabilitate one captive killer whale. How many human lives could have been affected by the same influx of cash? How many industries could have been bolstered by such an investment? How many alternative food sources could have been found with that amount of revenue?

I have spent the majority of my life trying to better understand the vast oceans of our planet and their inhabitants. My study of whales and dolphins have presented many fascinating hours as I attempt to understand the life they lead, but I would not for one moment place the value of their lives over that of a human being. I understand the hierarchy of living beings and respect it. While it is my choice not to consume the flesh of a fellow predator, I have the luxury of making that choice. I do not believe that other carnivores on the planet would have the same regard for me, nor would I expect them to do so.

While I may make a choice not to consume whale meat, I was raised in a culture where that is not the usual source of protein. If I had been born in another land, I'm sure I would feel differently. Before I could, in good conscience, ask another society to alter their way of life, I would have to be able to offer an alternative method for their continued survival; a method that would not only allow them to prosper, but that did not offend their sense of culture and history.

It seems as though the International Whaling Committee would have much more success if it remembered that the most basic requirement for cooperation is mutual respect.

Migration routes of western Pacific gray whales

line - Repoted routes

dotted line - Probable routes