- IS MAN THE CANCER OF THE EARTH?

Takao Nojima

Marine Mammal Research Institute - THE AMERICAN ANTI-WHALING POSITION : WHAT UNDERLIES IT?

Dai Tanno

Assistant Professor / Aomori Public College - THERE EXISTED A MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE GRAY WHALE IN THE WEST COAST OF THE JAPANESE ARCHIPELAGO

Koo-Byong Park

Professor Emeritus / Pukyong National University - HYPOCRISY IS THE GREATEST LUXURY

Koo-Byong Park

Professor Emeritus / Pukyong National University

ISANA Dec. 2001 No.25

index

ISANA Dec. 2001 No.25

IS MAN THE CANCER OF THE EARTH?

Whaling was an important industry for a long time for countries that are now commonly called industrialized nations. Further, the whale that occupies a peculiar position among mammals has been the object of interest of naturalists. The results of the research have provided important materials for comparative studies of mammals including man.

However, since some naturalists have highly rated the intelligence of whales (which actually has not been clarified to a full extent), a trend to regard whaling as an evil act has gained momentum in the Western world. Further, the wildlife protection movement intensified as a result of the spread of ecological education. At the same time, if whaling had continued without the adequate scientific research now available, it would certainly have caused a grave impact on the whale resources, thereby inflicting no small impact on the ecosystem as well.

John C. Lilly is one of the theorists who were instrumental in establishing the view that the whale has a high-level intelligence -- a view commonly used as one of the reasons to advance the anti-whaling cause. Lilly, a neurologist who studied neurophysiology, came to know the high-level communication capability of dolphins through his studies, and further went on to research the possibility of communication between man and dolphins.

The book "The Day of Dolphin", also presented in a film version, is said to be based on the theory of Lilly. The plot of the movie is that an attempt is made to assassinate the President by planting a bomb on the bottom of a yacht using a dolphin trained to communicate with human beings. Fortunately, this plan ended in failure. In a scene of a press conference at the outset of the movie, Dr. Derel says, after explaining the superb sensing capability of dolphins: "Dolphins have a few enemies. Sharks, barracuda, fishermen who exploit fishes randomly, and clumsy scientists who believe that the shortest way to know about the brain of the animals is to dissect it with a scalpel"

As one who specializes in anatomy, I find it hard to accept his last words because the foundation of biology lies in examining the structure of organisms.

Anatomical studies still have a lot to pursue despite their long history. Physiology, on the other hand, is designed to study functions, but functions and forms are 2 inseparably related to each other.

The results of physiological studies based on the latest methodology can be finally confirmed by the re-examination of the structure that is the place of its functions. Many important data on whale biology have been provided by anatomy. Here lies the significance of catch research.

What are the criteria of animal intelligence? An argument is often put forward to the brain weight or the proportion of brain quantity to body weight as well as the state of wrinkles (brain vallecula) which are observed on the surface of the brain. A larger number of wrinkles drastically increase the space and volume of the cerebral cortex covering the surface of the brain, and can provide for many nerve cells. As a matter of fact, many whales have more vallecula on their brains than humans do. Further, the density of the distribution of nerve cells in the cerebral cortex of whales is not inferior as compared with that of humans.

In the evolutionary process of animals, the nerve system has developed adequately to guarantee their life. Land mammals that live in herds have fully developed the capability to communicate with their companions.

"A twisted sperm whale and an anchor" carved from zelkova tree and red sandalwood,respectively.

"The shade is made of the baleen of the minke whale caught in the Antarctic Ocean.Three whales; right, fin and sperm whales showing in some Japanese old books, are drawn in Chinese ink on the unglazed pot.

"Konan Maru No.20" made of the lower jaw of the sei whale. 1/270 scale.

The expectation that dolphins and whales must have high-level intelligence seems to be based on an illusionary conclusion derived solely on the fact that they have relatively large brains and have adapted themselves to the special environment of the ocean.

Contemporary neurology has not progressed sufficiently so as to conjecture the functions of the brain from the form of the brain among animals which seem to be identical or similar. Although state-of-the-art technology is applied extensively, the studies on mental activities of man are still far from conclusive.

Diverse speculations regarding intelligence and mental activities by animals, it seems to me, are in many cases our own assumptions based upon whether we feel it is humanlike or not, when we observe the behaviors and reactions of animals.

All the animals including mankind must obtain energy to maintain their life and must procreate their posterity by the consumption of organisms, i.e. other living things. It is a right given to all animals equally, and is the fate of those subjected to predation. It is no exaggeration to say that animals have evolved through what they consume, and eating habits over a long span of time have allowed man to develop his dietary culture.

In each geological phase before the birth of mankind, nature repeated the cycles of destruction and reproduction. However, as a result of the explosive growth of mankind, as the latest comer, the balance of the ecosystem has been destabilized, with environmental contamination, at a rapid pace and to a grave extent, both directly and indirectly. The impact that has been, or will be, caused by man on the life on the earth can be likened to a cancer, which threatens the survival of mankind. Man should not allow himself to become a cancer cell because the death of the body also means the death of the cancer cell itself.

Ensuring the ecosystem (including the food chain) to remain in a sound condition and survive continuously is an important responsibility of mankind. It is, so to speak, to guarantee the future of mankind. Like other animals, man is also incorporated in nature. Its energy source, whether it is from the benefits from the wildlife or those from harvested or cultured resources, is in the end a benefit from nature that can be reduced to the limited amount of solar energy provided to the earth. Wildlife and cultured/harvested resources should be considered as one whole set of resources.

Living resources are renewable by means of reproduction. The focal point here is how to use the resources within an allowable scope without causing their decline.

Harvesting of whales should be allowed only when the whale resources can be managed sustainably at a certain level and compliance with regulations and a supervision system is ensured in the actual whaling activities. This is the view of the author, who approves the use of wildlife including whales as resources on an appropriate level.

THE AMERICAN ANTI-WHALING POSITION:WHAT UNDERLIES IT?

It is well known that the ordinary American public holds a strong anti-whaling position in spite of their meager knowledge about whaling, and that the United States is a leading anti-whaling country. Therefore, a variety of arguments have been put forward, a variety of questions have been posed and diverse responses have been given on this seemingly hard-to-understand phenomenon. However, those responses, at best, were within the range of speculation.

The survey team (led by Toshihide Hamazaki), of which I am a member, undertook to test those speculative responses and arguments. For this purpose, we had ordinary Americans participate in the survey as sampling participants (448 people from 12 universities throughout the United States) in 1998 and sought their response to our questionnaires. In what follows I shall report some of the findings obtained from analysis of their responses.

In the survey, we attempted to analyze responses to the following three questions.

- What factors prompt the respondents to take an anti-whaling position?

- Is the American anti-whaling position a form of "Japan bashing," as is often alleged?

- What would be the reaction of Americans to their anti-whaling position when an economic interest is involved?

We obtained the following answers to the above questions:

Regarding the first question, the elements cited as motivating the American anti-whaling sentiment were "a concern to protect the welfare of animals," "America-centrism regarding the whaling issue," and "the anthropomorphicizing of whales." As the fourth element, we also assumed "possible influence by the mass media." On the basis of these assumptions, we analyzed the data. But an analysis of results showed that there was little effect from the mass media. Rather it was indicated that the above three elements constituted the primary motivation.

In other words, with different degrees of influence, opposition to whaling was related strongly to the degree that one has a strong consciousness to protect animals, has a nation-centric view on the whaling issue and tends to anthropomorphize whales.

With respect to the second question, it was extremely difficult to verify the question whether "the American anti-whaling position is a form of Japan bashing" because when you ask an American whether he is opposing whaling to bash Japan, the likely answer is "no." Then we changed the question to asking to what extent whaling is tolerated for five peoples now known to be engaged in whaling: Icelanders, Greenlanders, Norwegians, Inuit's of the United States and the Japanese. The degree of tolerance obtained was in the order from (1) American Inuit, (2) Icelanders, (3) Greenlanders, (4) Norwegians and (5) Japanese. This order was exactly the same both for male and female respondents. It would be difficult to assert that "anti-whaling is a form of Japan bashing" only from the fact that the Japanese were placed in the lowest rank. However, as there is almost no difference among the 448 respondents for their reason to oppose whaling by those five peoples, the question remains "why Japanese were put at the bottom of the list."

The third question pertains to whether the "Not-in-My-Backyard" syndrome is also linked to the American anti-whaling sentiment, as is often pointed out. "Not-in-My-Backyard" syndrome is a kind of opportunism such as not caring about damage to the environment (e.g. those by industrial waste) as long as it happens in other countries, but fiercely opposing it if it happens in their own country. Of course, we did not ask such a question directly in the questionnaire. Instead we asked: "Suppose your friend is affected by the predation of fish by whales, do you still prefer protecting whales rather than fish?" The results of the analysis indicated that they would find more difficulties if their "friend is affected." This seems to suggest that the American anti-whaling position is a form of opportunism in that whaling has no economic stake for them. Conversely, it could happen that American would be less positive in their protection of whales once their economic interest is involved.

Human beings are prone to fight over rare resources. This cannot be avoided. But in case a conflict occurs over such resources, it is greatly to be hoped that the empirical, not speculative, approach will be taken so as to identify what elements further affect the conflict. Such an approach, it is believed, could lead to a better solution.

Anti-whaling rally taking place at a square near the 53rd IWC meeting site in London.

THERE EXISTED A MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE GRAY WHALE IN THE WEST COAST OF THE JAPANESE ARCHIPELAGO

The migration route of gray whales is a route where gray whales migrate between a breeding ground in the low-latitude area and a feeding ground in the high-latitude area. The migration route of the eastern Pacific stock (California stock) was a simple one, consisting of a single line. By contrast, that for the western Pacific stock (Korean stock, Asian stock), which was much smaller in stock size, was somewhat complex in the past. It has long been known that there were two migration routes: one in which the Korean stock (in a narrow sense), which constituted the mainstay of the western Pacific stock, migrated between the Okhotsk Sea and the South China Seas via the east coast off the Korean Peninsula, and the other in which the Japanese stock migrated northward and southward by passing along the coastal areas of the Japanese Archipelago. In the latter, the presence of a migration route in the east coast (on the Pacific side) of the Japanese Archipelago has been proved by the gray whales of Ichikawa, which is a archeological material, and the fact that gray whales had been caught off Wakayama and Kochi prefectures since the Edo Period. It is also proved by the records of ancient documents, which the author will cite in the following paragraphs.

A.G.Tomilin of the former Soviet Union considered that the gray whales that once were distributed in the east coast off the Kamchatka Peninsula and its vicinities belonged to the western Pacific stock. This means that the feeding ground for the east coast stock existed in the area. There is a view that the breeding ground for the east coast stock existed in the Seto Inland Sea, but this assumption has not been confirmed yet. I believe that the more likely area was the southern sea area of China.

Besides these, there existed another migration route in the west coast of the Japanese Archipelago, in other words, in the east coast of the Sea of Japan (East Sea). The gray whales, which used to migrate along this route, had been caught since the Edo Period off the north coast of Yamaguchi prefecture and the northwest coast off Kyushu, where whaling thrived from early times. Nevertheless, the presence of their migration route has been not only dismissed but also denied. But it can be confirmed by several documentary materials that a migration route did exist along the west coast. Because of the limited space allotted for this paper, I would like to present only a brief summary.

To begin with, let us have a look at documents from the 19th century. The "Illustrated Book of Whaling," by SankeyFujikawa, published in 1889, cited the words of an old whaler about “the moving way of the whalesEand said: "The whales of the Choshu region are the same ones as the whales in the Korean Sea ... The whales of Echizen and Kaga are the same with the whales of the Ezo region and many of them aree fin whales and gray whales. It is the same for the whales of the Manchurian Sea ... There are many fin, sperm and gray whales in the area off the Kurile Islands." It further said: "There are many humpback, sei, fin and gray whales in the Kishu and Toshu seas in early winter ... There are many fin, gray and sei whales in the area off the Yonewaki Village in Echizen, and the whaling season is set from March to May.EThese records tell us that there occurred many gray whales in the Wakayama and Kochi prefectures on the east coast and also in the Fukui prefecture (Echizen) and the southern part of the Ishikawa prefecture (Kaga) on the west coast. The fact that there occurred many gray whales in the area around the Kurile Islands seems to show that the east coast stock of gray whales made northward and southward migration along the islands.

The "New Discussion on Whaling" by Tatsuo Mishima, published in 1899, said, in explaining about the period and location of whaling, “that fin, gray and sei whales are found off the coasts of Echizen and Kaga between March and May.EAlthough it is not clear about occurrence of the sei whale, the occurrence of gray whales in the Echizen and Kaga regions coincides with the description of the “Illustrated Book of Whaling.E

The "Norwegian-type Whaling in Japan," by Kiichi Akashi (1910) published in the early 20th century said that “gray whales are divided into three groups: blue, red and white; and they are found in large number in Kaga, Noto, Awa, Kishu, Tosa, Hizen, and especially in the Korean Sea, and their peak period is from late in December to around January." This record, which appears to have high credibility, tells us that gray whales migrated between the southern part of Chiba prefecture and the Kochi prefecture, and were also occurred in the area from the Noto Peninsula to the northwest coast of Kyushu on the west coast.

Finally, according to Masao Nakamura, "Natural Resources of Niigata Prefecture," published by the Nakano Foundation and the Niigata Prefectural Office in 1925, it is said that "gray whales at times approach up to 2-3 chos from the coast, but their sighting is very rare in recent years." The description is simple 8 but the contents are concrete. It shows that gray whales migrated to only about 200 plus E300 plus meters (1 cho is about 109 meters) from the coast.

The above documents seem to prove the presence of a migration route of the west coast stock of gray whales along the west coast of the Japanese Archipelago. Although it is estimated that the breeding ground for the west coast stock of gray whales existed along the south coast of China, its feeding ground was certainly in the Okhotsk Sea. The west coast stock of gray whales entered the Okhotsk Sea via the Soya Strait.

Takashi Sato stated in his "Treatise of Whaling in Hokkaido" (an article contributed to the 221st issue of Bulletin of the Japan Fisheries Association in 1900) that gray whales were found most abundantly in Hokkaido, and it is difficult not to find them around the region. He further remarked on their movement that gray whales migrate gradually from the coast of Shiribeshi to the coast of Kitami from late in March to late in June. From this we come to know that the west coast stock of gray whales that migrated northward off the west coast of Honshu, moved probably feeding along, to the northeast coast of Hokkaido via the Soya Strait, after arriving along the southwest coast of Hokkaido in late March.

When we examine the logbook dated June 27, 1848 of the American whaling ship, Moctezuma, which came to the Sea of Japan in the spring of that year and moved to the Okhotsk Sea after completing its right whale catch hunting, it is recorded that they sighted some gray whales in the Soya Strait while they were passing the strait, and caught one of them. It seems that these gray whales must have been from the west coast stock on their way to the Okhotsk Sea. By the way, the fact that gray whales did not appear on the east coast of Hokkaido facing the Okhotsk Sea in early spring seems to suggest that east coast stock migrating northward moved northward to the eastern coast of Kamtchatka Peninsula and did not take the course to enter the Okhotsk Sea via the channel such as the Nemuro Strait.

<>The late Dr. Hideo Omura asserted that there was no west coast migration route. As the sole argument to support his view, Omura cited the fact that no gray whale had been caught in the Ine Bay in the past. Whaling had been conducted in the bay since the Edo Period, and whaling statistics by whale species for 258 years since 1656 had been made available. Dr. Omura asserted that gray whales did not migrate through the west coast, by pointing out that no single gray whale had been recorded in the statistics.Then a question naturally arises about where the gray whales, which had been caught off the north coast of the Yamaguchi prefecture and the northwest coast of Kyushu, came from. Dr. Omura understood that a separate part of the Korean stock (in a narrow sense) migrating southward along the east coast of the Korean Peninsula came across the Tsushima Strait. If it is assumed that there existed no gray whales migrating in the western coast off Honshu, there was no way but to conclude that it was part of the Korean stock.

The reason why gray whales had not been caught in the Ine Bay is another subject of further study. The western Pacific stock of gray whales has not gone extinct yet. Indeed, there is a sign of recovery, although at a slow pace. It is my belief that the west coast stock of gray whales will prove by themselves in the future the presence of the west coast migration route.

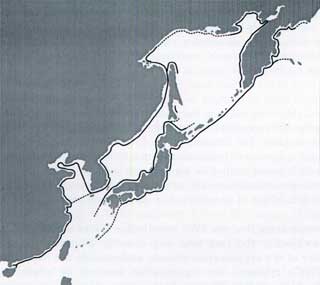

Migration routes of western Pacific gray whales

line - Repoted routes

dotted line - Probable routes

THERE EXISTED A MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE GRAY WHALE IN THE WEST COAST OF THE JAPANESE ARCHIPELAGO

The IWC and its members seem to have done the impossible once again. Namely, to speak out of both sides of their collective mouths at the same time.

The IWC refuses to apply one rule collectively. It seems vastly unfair and undemocratic to allow the native peoples of one culture to continue in the taking of cetacean species for food sources while refusing to allow other cultures to do the same. To argue that it is agreeable to allow Native Americans and Inuits to hunt because it is part of their heritage and culture, while ignoring the histories of Icelandic, Norwegian, and Japanese communities borders on political favoritism. In this day of dwindling food supplies, rising food costs, and rampant hunger in many parts of the world, it seems negligent to ignore the bounty that the sea might bestow upon us.

As distasteful as it might be to those with other means, the quantity of available food that the harvest of one minke whale allows could mean the difference between sustenance and starvation to a variety of native peoples. The industry of whaling alone assures the continued financial support of thousands that might have few other resources. The self-imposed limits that many countries have set upon the taking of endangered cetacean species allows that they are concerned and sensitive to effect of unrestricted or unregulated commercial whaling.

It would seem that the IWC could make better use of it's time by acknowledging the fact that any country interested in being a member of it's organization already understands the importance of the IWCfs mission. No organization succeeds by alienating it's members or possible allies.

We do not condemn the Hindu practice of refraining to slaughter cattle even though vast numbers of people could avoid starvation in countries that foster such beliefs. How then, does it make any sense to condemn countries that seek to sustain their people by continuing traditions that go back for dozens of generations? Surely, the ability to feed and sustain onefs family and community ranks the highest on anyonefs list of priorities.

While I would be among the first to look for other means of food production and financial independence, I could not in good conscience allow humans to suffer for want of practical application of natural resources. I honestly believe that some kind of median is possible while protecting the rights of all concerned.

As a scientist, I have watched while millions of dollars have been spent on the unsuccessful attempt to rehabilitate one captive killer whale. How many human lives could have been affected by the same influx of cash? How many industries could have been bolstered by such an investment? How many alternative food sources could have been found with that amount of revenue?

I have spent the majority of my life trying to better understand the vast oceans of our planet and their inhabitants. My study of whales and dolphins have presented many fascinating hours as I attempt to understand the life they lead, but I would not for one moment place the value of their lives over that of a human being. I understand the hierarchy of living beings and respect it. While it is my choice not to consume the flesh of a fellow predator, I have the luxury of making that choice. I do not believe that other carnivores on the planet would have the same regard for me, nor would I expect them to do so.

While I may make a choice not to consume whale meat, I was raised in a culture where that is not the usual source of protein. If I had been born in another land, I'm sure I would feel differently. Before I could, in good conscience, ask another society to alter their way of life, I would have to be able to offer an alternative method for their continued survival; a method that would not only allow them to prosper, but that did not offend their sense of culture and history.

It seems as though the International Whaling Committee would have much more success if it remembered that the most basic requirement for cooperation is mutual respect.

Migration routes of western Pacific gray whales

line - Repoted routes

dotted line - Probable routes